The Bakar Fellows Program: Ten Years of Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Community

By: Niki Borghei •

Our History

The Founding of the Bakar Fellows Program

“There is a major shift happening,” said Dr. Niren Murthy, Bakar Faculty Fellow and Professor of Bioengineering. “Twenty years ago, big pharma companies would not invest in anything that was not a small molecule. Twenty years ago, there was no way a grad student from my lab could raise two million dollars. But that’s actually happened to two people in my lab.”

Now, all of the new, exciting therapeutics are not small molecules; they’re cutting-edge technologies that are at their research stage. “This type of new investigational drug discovery is what academic labs are really good at,” he continued. “Somebody’s PhD thesis has the possibility of raising money for a startup.”

In 2012, the Bakar Fellows Program was established to promote the commercialization of research being performed on campus. Now in its tenth year, the program has helped produce over 15 startup companies, and it has accelerated the research of 64 faculty members and 50 graduate students, postdocs, and project scientists. Applicants come from a wide range of academic backgrounds including but not limited to bioengineering, plant & microbial biology, architecture, and physics. What the diverse group of Bakar Fellows have in common is a drive to create positive change by bringing their innovations into the world.

“The creation of the Bakar Fellows Program was a way to accelerate the translation of discoveries and innovations that were happening inside our research labs at UC Berkeley and get them out into the world to solve significant problems,” said Dr. Amy Herr, former Faculty

Director of the Bakar Fellows Program.

“The Bakar Fellows Program is unique primarily because it is geared towards funding people and projects that are not quite yet ready for translation out into the world, but they’re close,” she said. “We fill the gap for projects at stages that would otherwise struggle to find funding because they’re either too mature or not mature enough. When a project is at that point, there really is not much in the way of support to help boost the project and the people beyond that point. That is a rare attribute of this program, and I think it’s a testament to the vision of UC Berkeley and its supporters.”

Bakar Innovation Fellows

To maintain this vision, several changes were made to the program throughout its first ten years. As Dr. Murthy mentioned, the shift in the entrepreneurial world, particularly in biotech, meant options that were once rare for graduate students and postdocs are now much more accessible. So, in 2017, Innovation Fellows were introduced to the Bakar Fellows Program to help these researchers in faculty labs commercialize their projects. Innovation Fellows can be funded directly from a Faculty Fellow Spark Award or Bakar Prize, and they participate in Bakar Fellows workshops and networking events to provide support in their growing careers.

Dr. Tammy Hsu, who joined the Bakar community as a graduate student and is now CSO and co-founder of Huue, is one of these Innovation Fellows.

“In undergrad, I trained as a bioengineer and worked on engineering microbes and using biology to make a positive impact on the planet,” said Dr. Hsu, “This is how I approached my doctorate work in grad school when I joined John Dueber’s synthetic biology lab at UC Berkeley. John, a 2014 Bakar Fellow, had a project starting in the lab looking at a new way to dye textiles using biosynthesized indigo. This indigo dyeing strategy required fewer chemicals to synthesize the dye, and it didn’t require as many harsh chemical additives during the coloring process. In my Ph.D. work, I looked at how plants naturally synthesize indigo and mirrored those processes in microbes, designing microbes to produce color molecules the way plants and organisms make it.”

“As I was conducting research for the project, I learned more about the sustainability challenges in fashion, and that industry-standard indigo is made using chemicals harmful to people, and our planet. There was also interest from the denim industry even when the project was in early stages, which validated the market need for the technology. When I was nearing the end of my graduate studies, I applied for Berkeley’s Bakar Innovation Fellows Program, and it was a great jumping off point for my entry into entrepreneurship.”

Dr. Hsu shared that the Bakar Innovation Fellows Program was instrumental in helping her make the transition from academia to entrepreneurship. As a graduate student, the goals and mindset of academic projects are often different from those of startups, and the program helped prepare her for life outside the academic sphere. The Bakar Fellows Program introduced her to the variety of resources available as a Berkeley founder, from incubator space to accelerator programs to IP resources in the university ecosystem. She also found it helpful to meet other like-minded founders who were in a similar stage of startup growth as she was.

Just like our Innovation Fellows, Huue is just getting started. While their first focus is the indigo blue for fashion’s most polluting wardrobe item, denim, the potential and impact of this technology extends through not just other categories, like food and cosmetics, but also other colors of the rainbow.

“Since we spun the technology out of Berkeley, we’ve been focused on setting our process up for scalability. We are proud to have raised $14.6 million in funding that will help Huue grow and service additional denim brands at scale. Our focus in the next year will be to scale up our process to meet industrial levels of production, so we can meet the demands of our commercial denim partners.”

The Bakar Prize

The Bakar Prize, which was established in 2018, offers additional funding to Bakar Fellows who are making incredible progress with commercialization but require additional funds beyond the Spark Award.

“With the change in the program from a set five-year award to a two-phase award, essentially what we did was add a gate at the midpoint of the five years for those faculty and projects that look like they’re on a path towards commercialization,” explained Dr. Herr.

Dr. Murthy was a Bakar Prize winner who described the award as revolutionary for his mentality as an entrepreneur. “The Bakar Fellowship and the Bakar Prize did one key thing,” Dr. Murthy said in a video interview with the Bakar Fellows Program, “They made me think it’s possible that the people in my lab could do start-ups, that we could be successful at it. And that’s a huge change.”

Dr. Murthy was conducting research in collaboration with postdoctoral researcher Dr. Tara deBoer. They were developing a chemical amplification system called DETECT which rapidly identified bacterial drug resistance. This test would help healthcare professionals identify patients with high-risk infections, such as urinary tract infections, and get them the right treatment. This research has culminated in the company BioAmp Diagnostics, of which Dr. deBoer is now the CEO.

Our Present

Creating Community

It is not just entrepreneurship, however, that is at the heart of the program. It’s the people. The goal of the Bakar Fellows Program is to ultimately help people become the leaders in innovation they dream of being. From cancer treatments to affordable housing to gene therapies, the reason why these innovations aim to help the public is because the people behind them care. That is why the Bakar Fellows Program nurtures a human-centered culture through community building.

For Dr. Kathy Collins, a professor in the Department of Molecular & Cell Biology, joining the Bakar Fellows Program made entrepreneurship not only financially achievable, but it allowed her to see herself as the entrepreneur she would soon become.

“Part of it was an identity issue. I am an academic. I am a student mentor. I am a great teacher. I am head of the Division of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Structural Biology. I saw these things in my future. Was it ok to take time away from that? It was, but doing that with a community of people was crucial.”

Dr. Collins’ entrepreneurial efforts turned out to be a huge success. Her company, KaRNAteq, explored new enzymes that copy RNA back into DNA and developed a way to use them to detect diseases. But that was only the beginning.

“We had these enzymes that are good for our RNA sequencing application, but what they do biologically also presented a different opportunity,” she said. “This wasn’t something I envisioned when we started. We recognized the opportunity and we were able to get a big NIH grant for it, courtesy of the work we started with the Bakar Fellows Program. The second company is called Addition Therapeutics. It was the first UC Berkeley founder company in the Bakar Labs incubator at the Bakar Bioenginuity Hub.”

“Being part of the Bakar Fellows Program means having access to a community of people who have done something you want to do,” she continued, “‘How did you take this from your lab bench beyond your lab bench? At what stage did you take this beyond your lab bench? How did you negotiate?’ Talking to my Bakar Fellow colleagues and having them tell me I can do it and that it is worthwhile was something I needed.”

Commitment to Learning

In addition to being part of a compassionate, inviting community, Bakar Fellows are given an abundance of opportunities to learn from entrepreneurial experts. Whether it’s a workshop on how to put together a good pitch or a chance to speak with investors and lawyers, Bakar Fellows have the resources they need to thrive as entrepreneurs.

Dr. Ting Xu, Professor of Chemistry and Materials Science and Engineering, described the Bakar Fellows Program as something that “strives to provide fertile ground to nourish scientists and engineers.”

“I benefited quite a bit when preparing the application and presentation. Naturally, I thought about potential questions from review panelists. The process was quite important in my case as I took the time to think about where we would like to go and dug down in areas beyond technical ones. The process turned out to be more valuable than just winning the Fellowship and Bakar Prize. It had a long lasting impact, particularly in terms of how I position our scientific explorations in a broad spectrum of technological needs and social implications.”

For her Bakar project, she and her team worked on developing a solution to the plastic problem. “Although plastics are attractive, they are lethal to our vulnerable ecosystem. Even so-called biodegradable plastics degrade slowly, and the resulting small particles can be more harmful than the intact material,” she stated in her project description. As a solution, she and her team developed enzyme-embedded polymers to realize compostable plastics. This project was recently selected as the winner of the Falling Walls Science Breakthrough of 2022, demonstrating the commitment of our Bakar Fellows to create solutions that go above and beyond.

Our Future

A Change in Leadership

After many years of service to the Bakar Fellows Program, former Faculty Director Dr. Amy Herr stepped down to take on the role of Chief Technology Officer at the CZ Biohub Network. This year, Dr. David Schaffer stepped in not only to direct QB3 and the Bakar BioEnginuity Hub, but also the Bakar Fellows Program.

He described how he first became part of the Bakar Fellows community in 2018, “The first time I became involved was as an applicant to the program. A few years ago I ended up applying to this program because we had some technology that was promising, but we really needed resources to be able to advance forward. The research has advanced to the point now that it has led to two patents, and it’s going to be transitioned to a company over the next year or so. I was able to advance research that probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise thanks to the Bakar Fellows Program. Now I’m fortunate enough to be the director of it.”

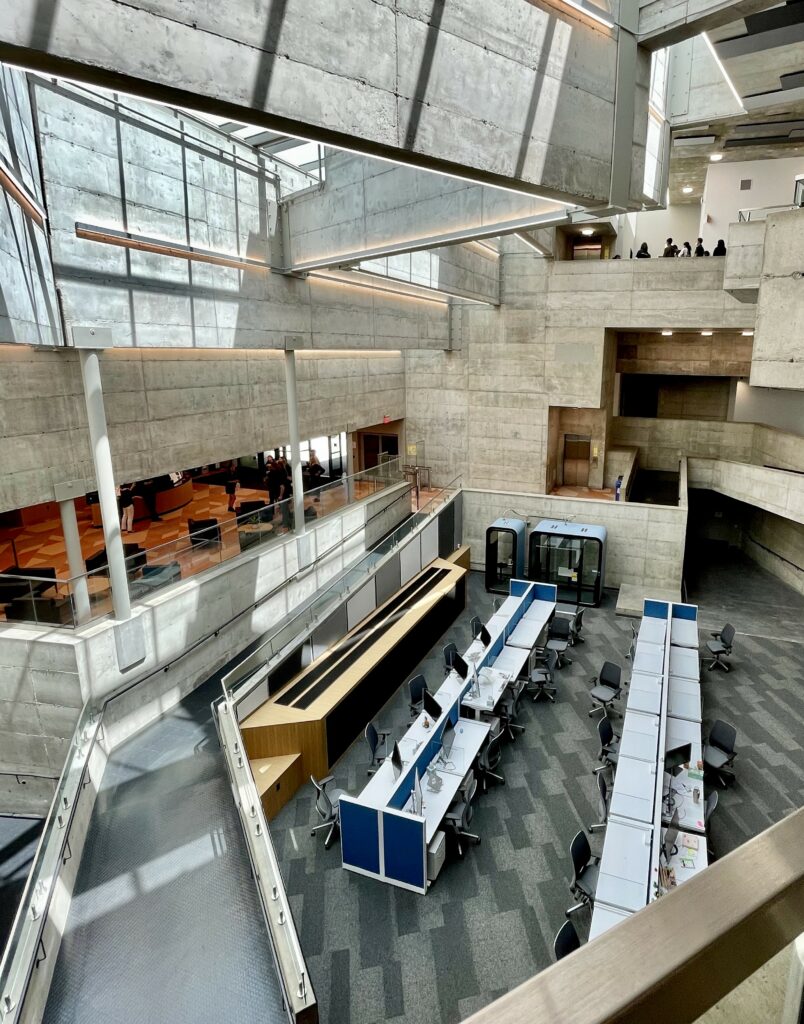

Bakar Labs at the Bakar BioEnginuity Hub

As for what he anticipates for the near future, he plans to see more interactions between Bakar Fellows and Bakar Labs. “While the Bakar Fellows Program offers the funding and community to support the translation of research, the Bakar BioEnginuity Hub and Bakar Labs provide the space for that. Bakar Labs is a great place to do technology translation, so I’d really like to have closer ties between them. Bakar Fellows can serve as scientific mentors for companies in Bakar Labs, and if Bakar Fellows decide to take the plunge and start a company of their own, then the presence of Bakar Labs makes that process much easier and much more accessible.”

He also emphasized, above all, the importance of community and education. “We’re going to start holding activities within the Bakar BioEnginuity Hub for Bakar Fellows,” he said. Whether it’s participating in workshops or meeting experts or, most importantly, learning from one another, there is no shortage of opportunities for our Bakar Fellows.