Arash Komeili

Plant and Microbial BiologyArash Komeili is a Professor in the Department of Plant and Microbial Biology.

Project Description

Synthetic Bacterial Compartments for Biomining of Metals

The traditional mining industry is facing a major crisis. Dwindling sources of easily accessible ores are increasing the costs of exploration and extraction of economically relevant metals. Meanwhile, the environmental consequences of extraction from ores are dire and present companies with costly cleanup protocols. To combat these problems, the budding “biomining” industry seeks to use naturally occurring microbial activities to liberate metals from minerals and subsequently isolate them with electrolysis. As a Bakar Fellow, Arash Komeili will leverage a poorly studied microbial phenomenon, the precipitation of metals in intracellular organelles, to engineer microorganisms capable of biomining important metals. His platform will create hybrid bacterial vehicles that will simultaneously produce iron-based magnetic particles as well as concentrate metals of interest. In this manner, specific metals can be sequestered from environmental sources and easily purified via magnetic separation.

Arash Komeili’s Story

Mining with Microbe “Animal Magnetism”

The bacteria thrive near the bottom of bodies of water, where oxygen levels tend to be lowest. They migrate down to the low-oxygen zones using their stash of iron like train wheels, traveling along the tracks of the earth’s magnetic field.

Arash Komeili, Professor of Plant and Microbial Biology and one of this year’s Bakar Fellows, aims to understand what controls and maintains the microbes’ novel traits. But a recent discovery may also lead to new ways to extract metals for commercial value or environmental cleanup. He described his research and the discovery that has led him in a new direction.

Q. How long have scientists known about these iron-mining bacteria?

A. They were discovered in the mid 1960s, and then essentially rediscovered about ten years later. But how the bacteria actually carry out this process has not been well studied. Over the last 25 years, researchers have determined that 20 to 30 genes are involved in the transport of iron, converting it to magnetite and storing in within the magnetosomes’ membranes.

Q. How does the magnetite actually orient the bacteria?

A. Each magnetosome creates as many as 20 magnetite crystals that form a chain, and this acts like a compass needle to orient the bacteria in geomagnetic fields.

Q. This seems like such an esoteric trait. How widespread is it?

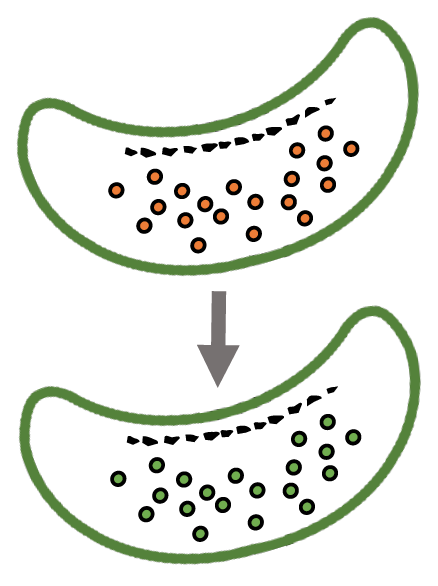

A. It’s unclear. Maybe about 30 species have been identified that contain magnetosomes. Recently, we discovered that there is a second type of iron-containing compartment in some of these bacteria. Initially we thought they were simpler precursors to magnetosomes, carrying out just the first steps of the process.

Then came the big surprise. This second kind of compartment contains iron, but it’s not converted into magnetite. It’s not magnetic at all. The iron has nothing to do with navigation. The storage is probably an adaptation to avoid iron starvation. And the iron is transported and stored in a much different way in these compartments.

Q. It sounds kind of like storing up fat for a lean winter. How did you discover this?

A. Meghan Byrne, a former postdoc in the lab, injected dissolved iron into the bacteria that contain magnetosomes and then tracked where the iron ended up. We naturally expected it would be stored in the magnetosome. But we found it in these distinctly different kinds of compartment that we call ferrosomes.

Then Carly Grant, a current postdoc, determined that only three to six genes are involved in iron transport and storage in ferrosomes, making them a much simpler system than magnetosomes.

Q. Where do you think this discovery might lead?

A. We want to gain a better understanding of this process. The Bakar Fellows funding will support more research on the protein transporters that ferry metal into the ferrosomes. Since only a few genes are involved, it will be much simpler to manipulate the genes to tease apart ferrosome transport and storage.

Q. How could this fuller understanding be applied?

A. We should be able to optimize the ferrosome size and number in the cell, and modify the bacteria so that ferrosomes are present at all times when magnetosomes are being made. Modifying the types of genes for ferrosome metal transport and when they are expressed should allow us to concentrate new metals of interest like gold, copper or manganese.

The mined metals in the engineered ferrosomes would be present in the same cells as the magnetic particles of magnetosomes, and because the magnetosomes are magnetic, the accumulated metals could then be extracted by magnets.

The genetic control could make for a kind of “plug and play” method to extract specific metals. The ability to concentrate different metals could be used to access valuable elements or to clear toxic metals from polluted water. This will require more research in the lab but it should be doable.