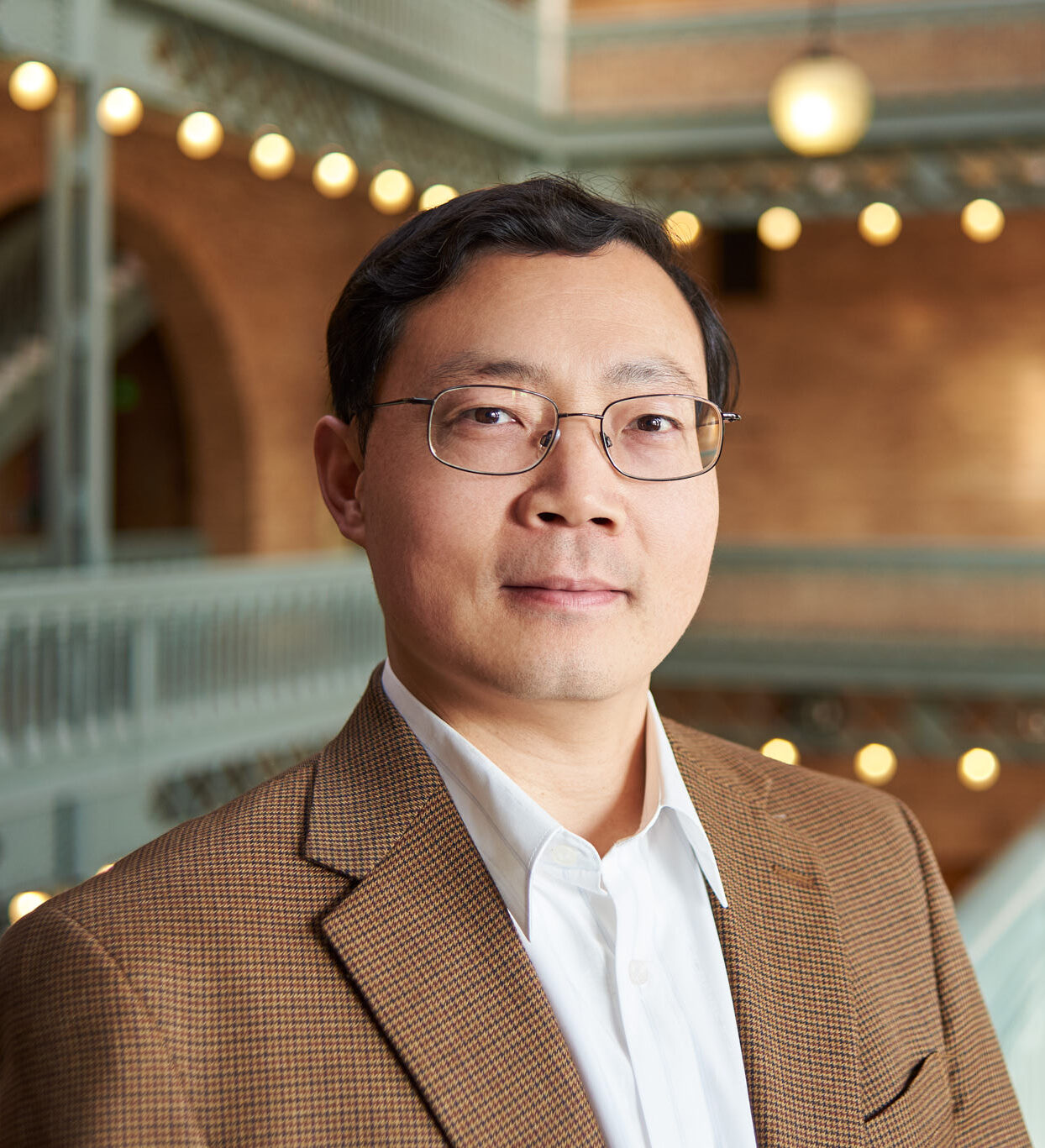

Junqiao Wu

Materials Science and EngineeringJunqiao Wu received his BS from Fudan University, MS from Peking University, and his PhD from UC Berkeley, and was a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University. He is currently a faculty member in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Co-Deputy Director of the Tsinghua-Berkeley Shenzhen Institute. Dr. Wu was a recipient of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) from the White House in 2013. The Wu laboratory explores novel materials properties and applications, phase transitions at the nanometer scale, and thermoelectrics and optoelectronics of semiconductor films, nanostructures, interfaces and composites.

Junqiao Wu was a 2020 Bakar Prize recipient.

Bakar Prize Project

Continued from the Spark Award Project detailed below:

Junqiao Wu’s Bakar Prize project is centered on addressing a building energy efficiency challenge. They aim to create a roof coating that can effectively regulate indoor temperatures, keeping homes cool during the summer and warm in the winter, ultimately reducing the energy consumption associated with heating and cooling.

Approximately 20% of total energy usage is dedicated to heating and cooling buildings. To harness the natural cooling potential of the sky, they have developed a solid film that autonomously adjusts its thermal radiative properties in response to varying ambient temperatures, requiring no external energy input. This temperature-adaptive radiative coating (TARC) efficiently absorbs solar energy and dynamically alters its thermal emittance. When temperatures are below 22 degrees Celsius, it maintains a low emittance of 0.2, retaining heat below the surface. However, when temperatures exceed 27 degrees Celsius, it switches to a high emittance of 0.9, facilitating radiative cooling of the surface. Simulations have indicated that TARC surpasses existing roof coatings in terms of energy conservation, particularly in regions with significant seasonal temperature variations.

Wu’s work, published in Science in 2021, has garnered considerable attention from the scientific community, industry stakeholders, and social media. Building upon this success, they have achieved significant milestones: (1) they’ve submitted two US patents, (2) secured a research grant from BASF, (3) obtained a STTR grant from the federal government in collaboration with industry partners, and (4) initiated an entrepreneurial venture with a dedicated core team. Ongoing discussions and partnerships with building and construction industries are actively underway.

This research direction represents a shift from their previous work funded by the Bakar Spark Award, where their focus was on enhancing the sensitivity of infrared sensing and imaging. Although that project yielded exciting results, resulting in publications and patents, its market potential was limited, and it faced substantial barriers to commercialization. Leveraging similar materials and working principles, they successfully transitioned their efforts to develop the TARC technology with the support of the Bakar Prize.

Spark Award Project

Multi-Smart Thermal Materials

We propose to develop, understand, and exploit a special class of phase transition materials as multi-functional coatings for smart thermal management. Thanks to a thermally-driven metal-insulator phase transition, these materials switch their thermal radiation reflectivity and thermal conductivity at the transition temperature, and the transition temperature can be tuned by the material composition. These unusual switching properties enable self-regulated, intelligent management of heat exchanges (both heat radiation and heat conduction) of a system with its environment for much improved thermal energy utilization. The technology would save a large amount of energy that is currently wasted due to poor heat management in those systems. For example, currently in buildings, ~ 50% of the energy consumption is used for heating and air conditioning, while in transportation, ~ 60% of the heat produced in combustion engines is directly wasted. If the coatings we develop would improve efficiency of these processes by only 5%, the net effect would save energy costs in the USA on the order of billions of dollars.

Junqiao Wu’s Story

When a car seat heats up on a hot day, it just gets…. hot. But some materials become totally transformed by the sun’s heat. They undergo a kind of Jekyll and Hyde reversal called a phase change. They turn from insulators to metals.

In theory, a compound that makes this radical change could provide a novel form of air conditioning. Early in the day, windows coated with the material would be transparent to infrared light, which accounts for about half of the heat streaming in with the sunlight.

But if the room warms beyond the desired temperature, the alchemy would kick in. The magic material would switch to its metallic state and start blocking infrared light, preventing the room from heating up any more. In effect, the sun’s heat would turn on the air conditioning.

Junqiao Wu, professor of materials science and engineering is exploiting the most remarkable of these compounds, called vanadium dioxide, to devise ways to cool buildings, winter-proof car engines, and even create novel sunglasses.

Actually, many compounds go through a phase change, but for most of them, the temperature at which this occurs is very far away from room temperature often above about 210 or below about -180 degrees Fahrenheit.

Vanadium dioxide changes phase at 150 degrees Fahrenheit, but by adding discrete amounts of the element tungsten to the compound, Wu can get the material to change phase at room temperature.

“By adding tungsten, we can ‘tune’ vanadium dioxide to change phase at precise temperatures,” he says. “If it’s tuned to change at room temperature, it will be transparent to infrared light in the cool morning, but opaque — blocking the infrared light — when the day gets hotter.”

The key feature, he says, is that it’s “switchable.” Every day, at the pre-tuned temperature, the window would switch from transparent to opaque – automatically, with no mechanical or electrical input.

Wu estimates that if such coatings improved the efficiency of heating, air conditioning and combustion in engines by just five percent, the savings in energy costs in the U.S. would be in the billions per year.

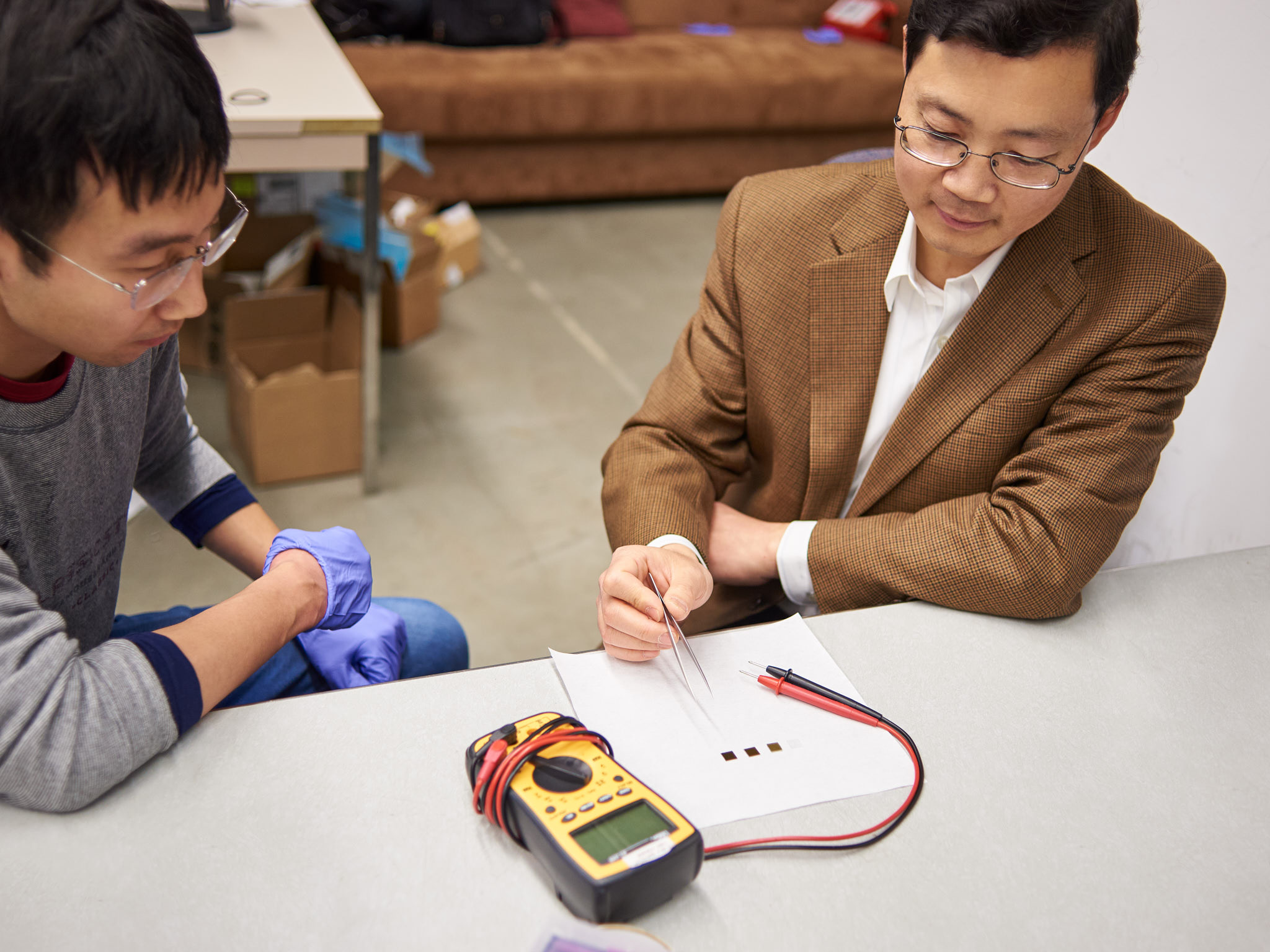

He and his postdocs have demonstrated the strategy with miniature prototype models of houses, one “building” window coated with the tungsten vanadium oxide and one not.

With funding from the Bakar Fellows Program he plans to ramp up the proof-of-principle experiments.

“I hope with the Bakar Fellows Program’s support, we can demonstrate the technology’s promise, and its practicality,” he says. “We want to secure a patent for the process we are developing and publish good papers to share the technology with other researchers in universities and in industry.” Wu makes the tungsten-vanadium dioxide concoction in extremely thin films, about 100 nanometers thick, or about one hundredth the width of a human hair.

In addition to regulating incoming infrared light, tungsten-vanadium dioxide can also switch from insulating against heat in one phase to conducting heat more in the other. If a car engine were coated with it, Wu says, the material would protect the engine from overnight freezing temperatures, but then switch to its heat-conducting phase when the engine is started to help warm up the engine.

The material also has an electrical resistance that is extremely sensitive to temperature. A slight temperature rise can drive the materials from electrical insulating toward conductive. This property, Wu says, can be utilized to make sensitive infrared detectors, called ‘bolometers’, that, unlike conventional ones, do not need special cooling.

Also on the drawing board: switchable sunglasses with lenses that could instantly change from light to dark with the flip of a switch, depending on the light conditions. In many professions, such as construction work or trucking, the sun’s glare can pose sudden and serious trouble. An instant change of the lens’s transparency, instead of a gradual shift as glasses currently allow, could help on the job, and even save lives.