Markita Landry

Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringMarkita Landry is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

Markita Landry was a 2023 Bakar Prize recipient.

Project Description

Genetic Engineering of Agriculturally Relevant Crops

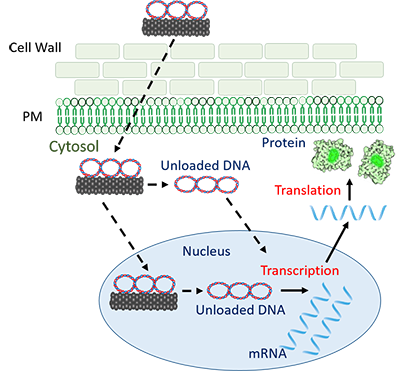

Plants are vastly underrepresented among the many biological systems in which genetic engineering is routine. Technologies to genetically manipulate plants yield random DNA integration into the plant genome, are inefficient, and require transgene segregation through laborious breeding if labeling as a genetically modified organism (GMO) is to be avoided. As such, with current approaches, it can take months to years to obtain and test a plant genetic variant. One main bottleneck facing efficient plant genetic modification is efficient biomolecule delivery into plant cells through the rigid and multi-layered cell wall. The Landry lab has developed a nanotechnology that enables high-throughput delivery of biomolecules to plants without requiring expensive equipment or refrigeration of reagents. The method results in transient protein expression without incorporation of foreign DNA into the plant genome, potentially avoiding classification of modified plants as GMO. Her Bakar Fellows Spark Award will enable her group to extend this platform to genome editing in plants of agricultural relevance such as corn, pepper, soy, rice, and tomato.

Markita Landry’s Story

It’s like a Trojan horse on an incredibly small scale, a vehicle designed to slip through the tough defensive wall of plant cells and deliver the potent gene editing system, CRISPR-Cas9. Once inside, CRISPR- Cas9 can snip out a targeted gene to boost crop yields.

(Photo: Mark Joseph Hanson)

The delivery vehicles are nanotubes — carbon cylinders just millionths of an inch long and a fraction of that across. Besides ferrying CRISPR-Cas9 across the cell barriers, nanotubes prevent foreign genes from inserting themselves into the plant genome – a potential regulatory drawback in crop genetic engineering.

Berkeley recently filed patents on the new nanotube technology to delete genes in crop plants without the risk of inserting new genes. Editing the genome of crop plants can boost such traits as disease resistance or drought tolerance. Since the new process adds no genes to the plant genome in the editing process, it conforms to non-GMO requirements in the U.S. and several other countries outside Europe.

The nanotube technology was developed by Markita Landry, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering. With support as a Bakar Fellow, Landry is now refining the technique and working with experts in agricultural science, business and other fields needed to reach the marketplace.

She describes the new strategy to safely improve agricultural crops.

Q. Why has it been difficult to genetically engineer plants?

A. A key feature of plant cells is their extra barrier – the cell wall that provides structural support, kind of like the skeleton in animals. The cell wall is hard to penetrate and makes it difficult to deliver genetic material.

Q. How is that barrier overcome in genomic work today?

A. Current methods shoot new genes through the plant cell wall or use a bacterium or virus to deliver them. The first approach, called biolistics, blasts through the cell wall, risking damage as well as adding multiple copies of unintended foreign genes into the plant genome. The bacterial and viral methods are pathogen-based, which triggers regulatory oversight, and also yield foreign gene integration.

Q. But your technique does introduce a foreign gene — the Cas9 gene. Isn’t that basically adding a new gene to the plant?

A. That’s the beauty of the nanotube approach. With other techniques, the Cas9 gene can become permanently integrated into the plant’s own DNA. But the nanotubes prevent this integration. The Cas9 DNA, when delivered with carbon nanotubes, is prevented from becoming a part of the plant’s genome.

Once the CRISPR-Cas9 is delivered, the plant’s genome translates the Cas9 gene into the enzyme that can precisely cut out a specific gene. But the Cas9 gene remains separate from the plant’s genome. The cell soon tags this foreign DNA as “non-self” and degrades it. Cas9 leaves no trace, except the gene it targeted for knock-out.

Q. How can the nanotubes get through the cell wall without causing damage?

A. Well, the first answer is they’re incredibly small. Their stiffness is also important – like the difference between trying to push a needle through a pincushion rather than a string. We’re trying to understand the effects of other features, like the nanotube shape and its charge.

Q. Are these “off-the-shelf” nanotubes, so to speak?

A. No, without any changes, DNA wouldn’t load or bind to the nanotube. We have developed surface chemical changes that allow the genetic material to adhere to the nanotubes.

Q. How did you come to discover that nanotubes could be used in this novel way?

A. Initially, we were using nanotube sensors to image plant signaling molecules. But it didn’t work. We found that the nanotubes slowly went through the cell walls, making the imaging difficult. It turned out there was nothing in the literature about things going through the tough plant cell wall. So, we decided to switch the project into gene delivery.

Q. How does the Bakar Fellows award support your research?

A. My PhD is in physics, and my focus has been more basic research. The Bakar support is allowing us to connect with experts way more knowledgeable in the agricultural biotech sector — talking with scientists who know what genes make the most sense to target, what crops are in most need –and the practical and regulatory issues that affect moving the nanotechnology into agriculture.

Our Bakar Innovation Fellow, Eduardo González Grandío, is leading our lab’s efforts on Cas9 delivery to crops. Eduardo is now working on genome editing in rice via nanotube-based delivery of CRISPR DNA plasmids. We hope the nanotube technology can make its way into agriculture within five to ten years.